In Cajamarca, nature's splendor is close at hand and readily

accessible to visitors seeking the charms of this beautiful land. In

1532, when 160 Spanish soldiers led by Francisco Pizarro arrived in Cajamarca, fatigue and

greed limited their profits: one room of gold and two of silver. The rooms were never

truly filled because the Spaniards made the mistake of executing Atahualpa, the last

sovereign of the Inca Empire before his servants had delivered as much ransom as had been

promised. Nevertheless, this land still holds its true treasures, some deep within its

memory, but most readily available.

Cajamarca is colored green in my memory. This beautiful north Andean valley seems to

retain the moisture from an earlier era when it was a big lagoon. One by one, the

valley's hillsides and meadows slip through my mind in a palette of colors scattered with

yellow broom flowers. Small white clouds only intensify he clear blue of the sky, and the

sun shines as radiantly as when he was once worshipped.

But I must not forget that the sky is overcast during the first months of the year and

Catequil, the God of Lightning, thunders in the heights and anoints the inhabitants, the

crops in the fields, and the livestock with rain. In Cajamarca, the splendor of nature is,

indeed, close at hand and readily accessible to visitors seeking the charms of this

beautiful land.

Every year armed with soft drinks, sandwiches, toasted corn, fruit, and the company of

good friends, I set off on a symbolic pilgrimage up two of the sacred mountains where the

wind swells its lungs and various animal and plant species announce that we stand before

true shrines to our oneness with nature. There we find the Cumbemayo River (named for the

legendary Cumbe people who inhabited the valley) at 3,600 meters above sea level. We

arrive weary, but ready to be revitalized by the vision of a spectacular petrified forest

known as Frailones (Big Friars), due to the colossal rocks shaped by the ages into

`friars.´

In Cumbemayo, the famous aqueduct carved entirely in stone attests to an advanced

pre-Inca civilization, whose mathematical and hydraulic knowledge never ceases to amaze

visitors. In the archaeological complex, a series of ceremonial altars and indecipherable

petroglyphs have been preserved. The ascent on foot is not difficult, although tourists

prefer to go by car. The descent is easier. I recall that as children we used to descend

the Cumbe like wild horses, running from the rain, from nightfall, or from the possibility

of being turned to stone. Now, as we look back, the sunset stretches its multi-colored

rays past us into the dusk. On the opposite side of the valley, over the summits of the

Callacpuma or Pumaorco (hill of the puma), the moon rises large and pale, trailing her

veil of stars and constellations, to illuminate the cave paintings left there by early

man. The hill lies along the route from the Baths of the Inca, -whose waters are among the

most famous in Peru to the picturesque town of Llacanora also known for its waterfalls.

To the south, on the way to the villages of Namora, Matara or Jesús, the countryside

varies cheerfully with the seasons and types of crops. The planted fields stretch out like

an endless expressionist painting crafted by thousands of farmers and teams of oxen.

Molle

trees, weeping willows and penca trees line the roads.

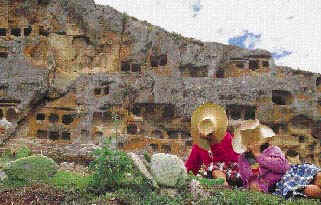

During the feasts of the patron saints, a sea of hats invades the streets. Here artists

and craftsmen meet with their stories, foods, music and typical crafts in straw, wool,

leather, clay and stone. They discuss their affairs in the shade of adobe walls and

proffer their goods, the legacy of ancestral Andean cultures.

Cajamarca invites one to serene contemplation. It is a sea of tranquility

and repose, a people living by the strength of their labor and the vitality of nature.

![]() http://www.rumbosperu.com

http://www.rumbosperu.com