Lima is hard to leave. The various deities and demigods

must be propitiated first. Today there were mysterious packages and envelopes to be

dropped off, vital keys to be left somewhere, a dog to cuddled, someone’s granny to

be kissed goodbye, and a construction foreman needing funds for cement. So it went: stops

in San Isidro, Miraflores, Barranco, until at last we were on the Panamerican highway,

heading south

After Pisco, the Panamerican pulls steadily away from the coast. At Ica it is more than

50 kms. from the Pacific. This was the blessing we sought, because if anything united the

motley crew of this 1986 Land Cruiser, it was an urgent need to escape from Lima-style

modernity for a while. David worked in investment banking, Rosi, in the U.S. embassy,

Claudia, at a diary which someday become a novel, while I, the last, toiled at various

rogue enterprises, among them photography and the writing of tales.

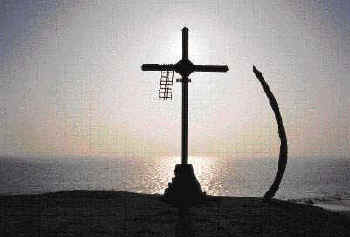

A cross and one whale rib (the other one was stolen)

mark the heights of Punta Carhuas.

Beyond Ocucaje, as the Panamerican peeled away south-eastward, we took a turn-off that

maintained our southerly drift along the valley of the Rio Ica. The change was abrupt. Now

we were following tracks that wandered across hard-pack desert. They were well-used and

wide, but meandered in every direction, splitting at random. They were used mainly by

fishermen who patrol the coast, inshore netting and diving. There are no maps to these

routes. Even local people tend to get lost.

We were been joined by Alberto Benavides, another committed escapee from civilization,

with his late-model diesel Toyota pick-up. Now we were five. Six, if you counted Wayra,

his trusty hound/best friend. We stopped for lunch at Alberto's desert retreat in the Ica

valley, and pressed on across the desolate landscape, aiming for Puerto Caballas, near the

mouth of the Rio Ica. We found plenty of car tracks, but one after another they came to a

dead stop at the edges of steep escarpments, or in fresh mounds of impassable sand. This

continued all afternoon, while precious fuel vanished in smoke.

As evening approached, the distant southern end of a

long slope to the sea revealed the curved bay and scattering of fisherman's shacks at

Puerto Caballas. The promontory was besieged by raging winds and huge waves. Reaching its

shelter, we were instantly consoled by the sight of a fresh catch of lenguado. The

fishermen agreed to cook some up for us in their grubby shack.

As evening approached, the distant southern end of a

long slope to the sea revealed the curved bay and scattering of fisherman's shacks at

Puerto Caballas. The promontory was besieged by raging winds and huge waves. Reaching its

shelter, we were instantly consoled by the sight of a fresh catch of lenguado. The

fishermen agreed to cook some up for us in their grubby shack.

They were divided as to whether we could get much further north by driving along the

beach. Some said yes while others interjected that there were impassable dunes Punta

Olleros. We elected the optimistic advice, and set off with the raging wind at our rear.

Cleaving to the narrow strip where ocean meets beach, we drove northward flat out barely

outrunning the grip of the soft, clingy sand.

We crossed the dry mouth of the Rio Ica as night fell. This river rarely runs, and only

for brief periods during the Andean rainy season. Had we come three months later we could

not have crossed it at all; during the El Niño of '97-'98 it became a muddy torrent,

flooded the city of Ica, and rushed madly to the ocean for three long months. At

last we found a northbound passage through the hills, and later still spotted a patch of

dull green in the distant north-east. "That's Puerto Huamaní" yelled Alberto:

his retreat in the Ica valley; the very same place where we ate lunch yesterday.

The next day, having refueled, we struck out again, in a less ambitious effort reach

the coast at Punta Lomitas, some 25 air kms. North-west. This time the route was fairly

clear, bounded by a broad valley. Below us and far off lay Punta Lomitas, a bare point

thrusting into the ocean above white skirts of surf. We reached the beach, nursing a

reasonable suspicion that we could proceed unimpeded for some distance north. We were

using Ricardo Espinosa's guide, Peru a Toda Costa, which indicated that a good part of

this route was "only for the Experienced,´ and that an impassable stretch of dunes

would block our way at Punta Azua, some 20 air kms. north. But Espinosa's guide was

written for those traveling north-south. The prevailing south-westerly winds created a

gentle southern gradient to the dunes, while leaving a steep drop-off at the north edge.

Traveling northwards, we reckoned we could climb those south slopes. If we were wrong, we

would have to backtrack to the Ica valley yet again.

![]() http://www.rumbosperu.com

http://www.rumbosperu.com